| The Vikings are Back! From a 1982 newspaper article about the reunion. |

Wes' overall plan was to record an album which he would produce, sell it to a major label, and put the band on tour.

So with the money in place, in September of 1983 we began drawing our salary and all immediate attention was placed upon the all-important record album. Our first task was to select the songs we would be recording.

| The Vikings are Back! From a 1982 newspaper article about the reunion. |

At early meetings Wes had made it clear that if he were to be involved in the project he must have complete control over every aspect of the venture. This included the final selection of songs for the album. He spent much of the summer gathering material from publishing companies in L.A., New York, and Nashville. For weeks Wes talked by phone of the great songs he was getting.

In September Wes, his wife, and newborn baby moved into a suite at Roanoke's Patrick Henry Hotel for a month in order to choose and rehearse the album material with us. Upon his arrival we and the board of directors ceremoniously presented him with his $50,000 check.

The next day Wes and the band gathered at my condo to hear the music he had selected. Farrell arrived armed with a multitude of cassettes sent by the various publishing companies. He had chosen about 30 songs from the ones submitted to him; we would choose 10 of those for the album.

The first song he played was called Ain't No Way. The demo had a distinctive folk-rock feel and we liked it a lot. After that, we were in for a surprise: most of the demos were high-power rock; the demos themselves were heavily produced and many sounded like finished recordings.

While we liked much of the material, we questioned our own ability to handle it. We weren't a rock 'n' roll band ... we had envisioned something much different than what we were hearing.

Wes argued that the quickest way to pay back our investors would be to have a hit contemporary rock song. I could not disagree with that. And Wes Farrell was the man with the track record; indeed, many of the investors had become involved because of Wes' presence in the venture. We had hired him to do the job and I felt we had to trust him with it. Also, I had already begun to think about how we could tone down the demos and do them in a way more suited to us. Rock or not, there were some pretty good songs there.

We rented a comfortable building, took in some furniture and a piano, installed a phone, and settled down to rehearse the songs for our album. We chose the 10 that we liked the best and were careful to arrange them "Vikings style," with lots of up-front harmonies and a more laid-back feel than the high-power demos. Wes was with us almost the whole time, having set up an office at the studio.

During this time Allen grew a beard and Fred got a perm. In an attempt to get ourselves in shape we jogged every morning at the track inside Victory Stadium. On one occasion Allen, Fred and I were running when Fred fell back for a minute; he reappeared smoking a cigarette as he jogged. To this day I've never seen anyone else smoke and jog at the same time, even in a movie.

| Reunion in 1982! Allen, Leroy, Joy, Tommy, Ralph, Fred, Ann, Tyler, Lane. Photo used for publicity for the show taken during a rehearsal. See the ad at the bottom of the previous page. |

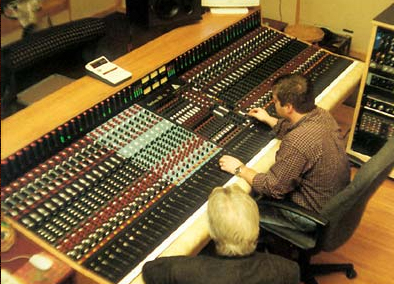

After about a month of rehearsals, Wes declared us ready to record. He booked studio time at Nashville's Treasure Isle Studio, one of the best-equipped and most-used facilities in the city at that time. Through the studio personnel, he also booked the engineer and studio musicians that would play on the album. These players turned out to be some of Nashville's best; indeed, some of them have become legendary. I know how difficult it is to book these very busy people. I'm sure the name Wes Farrell helped us in this instance.

I had known from the beginning that we would be playing our own instruments little, if any, on the album. Studio recording is a practiced art and hiring experienced studio musicians is common with many artists.

So, in October of 1983, about a year and a half after the reunion concerts, we set out for Nashville. Believing that comfortable hotel arrangements were essential for quality work, we booked five single rooms at the Nashville Mariott, a fact that did not make Sands Woody, the corporation treasurer, at all happy when he received the final bill.

We spent a couple of days getting settled and acclimating ourselves to the Nashville environment. One day I ran into Sylvester Stallone in an elevator at the Mariott ... he was in town filming the movie Rhinestone with Dolly Parton. The Marriott lounge was a popular nightspot and we spent lots of time there. Our spirits were high. Fred's license plate read "TV Star" and I remember that he always got some attention when he wheeled into the Marriott's parking lot.

The first five days of the recording session were to be spent laying down the music tracks; our job was to sing "scratch vocals" (rough vocal tracks which would not be retained) while the musicians recorded.

I kept a diary for a short amount of time. Diary excerpt from 10/13/83, the first day of the session: "Today marks the culmination of a year and a half of working, planning, worrying, not sleeping, thinking: today I begin work recording an album with Joy, Allen, Fred and Leroy. The Vikings. Roanoke. I am excited, I am uneasy, I am cautious, I am open-minded ... We have imposed upon friends who have in turn taken chances financially to back us ... We will do our best."

| Bert Berns and Wes wrote Hang On Sloopy. |

A trifle melodramatic, perhaps, but emotional levels were high for all of us.

Day One in the Studio: We arrive an hour before the session. The cartage companies (which are hired by the musicians to transport their equipment from studio to studio) have already delivered the massive amounts of the players' gear. Our easygoing and very capable engineer, Willie Pevear, is working on the drum sounds with drummer Dennis Holt. The musicians arrive one by one and introduce themselves: pianist David Briggs, who has played on sessions for everyone from Presley to Dylan to McCartney; guitarist Paul Worley, one of Nashville's best known players and a producer himself for some of Nashville's biggest names; and three other heavyweight musicians: synthesizer player Mike Lawler, guitarist Jon Goin, and bassist Michael Rhodes.

The atmosphere is professional and businesslike. Pevear places each musician in the studio and works to achieve the best sound for each individual instrument. When he is happy with the overall sound, I distribute the chord charts for the first song, All in the Name of Love.

Now it's Wes' turn. I am very curious to see how he handles the session.

Wes plays the demo of the song several times for the musicians, who make notes on their charts. They take their places in the studio and we go to a vocal booth to sing the scratch vocals.

It was at this point in time that I realized that the tracks were not going to be what I had envisioned. Wes did not encourage any toning down of the original demo. In fact, he actually used the arrangement already on the demo which the musicians enhanced and made even more high-energy than the original. I was in awe of the musicians' talents and the music sounded great, but doubt and worry were beginning to form in the back of my mind. I wondered, where was Wes when we were rehearsing our vocal arrangements? Surely he did not believe they would fit these music tracks.

Even with my doubts, I became caught up in the moment. The musicians were really into the music and it did sound good.

I forced myself to focus upon one thought: this just might work.

| Wes first saw The Vikings at this City Market show in Fall 1982. Tommy, Joy, Ann, Fred, Lane. |

It became obvious early on that Wes would not even consider any suggestions regarding the session. He angrily put down any idea or suggestion that we had. As mentioned, he insisted upon complete control ... and he meant it.

As the week progressed, I became increasingly disillusioned with Wes' method of producing, especially with the way he handled the musicians. He was in his own world and at times he was an absolute tyrant. He drove musicians to their limit and less professional players would have fallen under the pressure.

But, even with my misgivings, I generally enjoyed the week of recording instrumental tracks. We became friends with the players and enjoyed off-hours with them. Our scratch vocals, especially Joy's lead work, seemed to sound good with the tracks though it was impossible to know how they would fit in the end.

Diary entry, Saturday, 10/15: "On day two, Joy came alive. The musicians were impressed ... we feel good."

And the guys really did seem impressed. There were some rumblings that this had the potential of being a very good album. Except for some tense moments with Farrell, I had to admit that the music was sounding good. I bit my tongue and assumed a positive attitude.

At the end of the sixth and last day of recording music tracks, we threw a champagne party for the musicians at the studio. This was to be our last festive day for awhile.

Now it was our turn: It was the first day of recording vocals. As I had anticipated but had not wanted to believe, our vocal arrangements simply would not work with the music tracks. There was much frustration and anger exhibited over the next few days; I remember that at one point I tore off my headphones and threw them across the studio. Wes yelled a lot and discouragement was settling in.

After several days of attempting vocals and accomplishing nothing, we returned to Roanoke for the purpose of re-working the vocals to suit the tracks.

| Wes wrote The Beatles' Boys and Twist & Shout. |

We came home discouraged, frustrated, and panicked, with our tails between our legs. Investors and friends were naturally interested in how things had gone. We were forced to make lame excuses.

We retreated to our studio for two weeks of intensive rehearsing.

In December of '83 we returned to Nashville for the rescheduled vocal session. This time we stayed at a tiny motel close to the studio; the Marriott's luxury was history for us.

In the meantime Wes had hired Tom Bahler, a vocal arranger from L.A., to help us with vocals on the recording. We were skeptical at first, but the skepticism soon turned to admiration. Tom Bahler played a big role in saving the session.

Here we see displayed one of Wes Farrell's strong points: he did know talented people and was able to get them.

Bahler had been one of the recording voices of The Partridge Family, with whom Wes has been associated during their peak years. At the time of our session Tom was one of Quincy Jones' principal vocal arrangers. In 1983 he was riding high with recent successes: he had worked with Michael Jackson on the Thriller album and had been vocal arranger and background singer on Billy Joel's Innocent Man album which produced such hits as Uptown Girl and Tell Her About It. And later, in 1986, Tom played a key role in arranging the voices for We Are The World.

On one occasion, while I was giving Tom and Wes a ride from the studio, Uptown Girl came on the radio and Bahler sang along; it was an eerie feeling hearing this familiar song while listening to the background vocals being sung live from the back seat by the guy who actually did them.

Bahler knew what had to be done and took charge: one by one he listened to the tracks, arranged the background vocals, and chose which band members would sing on each, based upon vocal range and quality.

Bahler knew how to make the vocals fit and we were behind him. He was an intelligent and talented person, a bright spot for us.

| Another shot from the City Market gig: Allen, Ralph, Tyler, Tommy, Joy. |

Upon completion of the background vocals, it was time to record the leads. Because of the range and energy of the material, Joy was to sing lead on all but three songs.

Wes was relentless in his approach; he pressed Joy to sing for many hours at a time with few breaks, which on one occasion caused her to lose her voice. As usual Wes wouldn't listen to us; only when Tom Bahler stepped in would he end a session.

During this trip Wes hired a costume specialist named Vickie Graef to sketch individual stage outfits for the band. She faithfully followed his directions (which included dressing the guys in old Western-style dusters) but Wes kept changing his mind; at one point he instructed Vickie to "light up Tommy's buttons and shoes." Envisioning myself looking like the Robert Redford character in The Electric Horseman I called Vickie and asked her not to light me up. She laughingly replied that she had no intention in doing so.

Finally the vocal session ended ... and it ended on a high note. Everyone seemed pleased, especially Tom Bahler. That made us feel good and a hint of optimism returned. Wes, Willie Pevear and I mixed the songs and, in Wes' words, "We have a rekkid."

But we didn't have a record label.

It was time for Wes to approach the various record companies in order to gain a national record release. He assured us of his contacts and instructed us to go home and wait.

So we did. We waited. And waited. And waited...

The year 1984 was a lesson in frustration and sometimes comedy. In January of that year, Wes sent a photographer, Peter Brill, and a make-up artist named Rique from Nashville to take band pictures for publicity and for the album cover.

We met in a room at the Patrick Henry Hotel. Rique, who later became one of Nashville's premier hair stylists, gave us haircuts and proceeded to help us each attain our individual image for the upcoming picture sessions.

| The board at Treasure Island Studios, Nashville. |

Our first evening was spent in local photographer Greg Vaughn's studio; this was interesting and fun since we had never been in a professional picture-taking session with the photographer telling us how to move and Rique constantly jumping in to add makeup, dab our foreheads and adjust hairstyles.

The next day we went to a farm for some outside shots. This was grueling because it was very cold; the photographer's flashbulbs kept freezing up ... and so did we.

We moved from there to Joy Ellis' family business, M&S Machine Shop in Salem. Since the album was to be titled A Little More Fire it was thought that there should be fire and sparks in the picture. A set was erected in the shop and Joy's dad and other M&S employees stood by to shoot sparks onto the set utilizing a huge mechanical grinder.

Someone waited in the wings with a bucket of water in case anyone's hair spray should catch on fire.

We were told that the sparks would not hurt when they hit us. We took our places on the set, the photographer aimed, and someone yelled "Start sparks!" The deafening sound of the grinder began and sparks showered down over us.

As soon as the first spark hit each of us, we were out of there. They felt like fresh sparks from a very hot flame. By the time the photographer had time to squeeze the shutter, the set was mostly empty: his first picture shows the set with a few retreating arms and legs.

When we knew what to expect, we somehow managed to endure the sparks until four in the morning.

The following day we had some final pictures taken at Allen's house against a blank wall in his living room. All told, hundreds of pictures were shot. Most were never used. The one which would ultimately be the album cover was taken ... you guessed it ... in Allen's living room.

Wes insisted that we take dance lessons. We had never moved at all on stage and, since we had a rock 'n' roll album we had to learn how to do rock 'n' roll moves.

Imagine four 39-year-olds and a 43-year-old trying to learn rock 'n' roll moves.

A local dance instructor, Vickie Bryant, set up a special class for us only ... two hours a day, five days a week. Vickie was very patient but she must have suffered. I tripped constantly on the flat floor. Fred got dizzy with every turn. Leroy always seemed to do the opposite of everyone else; when we were supposed to look left, Leroy looked right; when we were supposed to kick our left leg, Leroy's right leg seemed to naturally go up.

Also, Steve Musselwhite introduced us to aerobics. We joined the Roanoke Athletic Club and our presence must have created some stir with the in-shape aerobics regulars. Anyone who knew Fred, who never really woke up until noon anyway, can try to envision him in a 9 a.m. aerobics class. Not pretty.

| Another shot from the City Market gig: Leroy, Allen, Tommy, Steve Hulse (a friend from Atlanta on keyboard), Ann, Fred, Lane. |

Our previous rehearsal studio was no longer available so we took up residence in a vacant building owned by Sands Woody's wife, who agreed to let us use it until it was sold. The building lacked heat and air conditioning; in the winter months we huddled around a couple of kerosene heaters and during the summer we sweltered.

This was an especially difficult time. Since there was no album deal we couldn't afford to hire the necessary band members .. a drummer, lead guitarist, and bass player ... thus we couldn't perform in public. Because we were on salary, we were obligated to do something; so our days ... for over half of 1984 ... consisted of dance class and aerobics in the mornings and rehearsals ... vocal rehearsals, since we didn't have our needed sidemen ... in the afternoons.

We somehow managed to keep our sense of humor through all of this. Fred came up with a monologue that was hilarious when he told it ... it went something like this:

Fred's conversation with stranger at bar:

"What do you do for a living?"

"I'm in a band."

"Oh? Where do you play?"

"Nowhere."

"You don't play? Then what do you do?"

"Take dance lessons, do aerobics."

"Do you rehearse?"

"Yeah."

"What are you rehearsing for?"

"Our big concert."

"When is it?"

"Don't know."

"What kind of band is it?"

"A rock band."

"Who plays lead guitar?"

"No one."

"Drums?"

"Nope."

"Bass?"

"Unh-uh."

"Have you ever recorded?"

"We did an album?"

"Which label?"

"None."

"Where did you record?"

"Nashville. Big production. Top studio. Top musicians."

"What did you do during the session?"

"Drank beer, smoked cigarettes, watched TV."

Wes constantly assured us by phone that a record deal was right around the corner. In the summer of '84 he instructed us to hire the additional band members. After two months of searching we signed three fine musicians: Bruce Wall on drums, Ray Wilkes on lead guitar, and Audie Stanley on bass. We began rehearsals with them in September of '84.

| Roanoke in 1983: Leroy, Fred, Allen, Joy, Tommy. |

So we finally had our band together, but still no deal. Wes had unsuccessfully approached almost every major label in the country, and finally settled upon a distribution deal with IDN, an independent distributor in New York. We formed our own label, "Big Byte." This naturally was not what had been hoped for, but the album would be nationally distributed and, more importantly, it was finally being released.

We decided to play some small local engagements to get in shape fur the big upcoming Roanoke concert that would coincide with the record release. We played at a club in Lynchburg that appealed mostly to teens. It was a disaster. We quickly learned that the young people who frequent this type of club want a certain kind of current, danceable music .. and if they don't get it they let you know. This was exemplified a week later at Roanoke's 2001 nightclub. Between sets, while I was in the bathroom, a kid asked if we were going to play any more that night; when I said we were, he replied "Oh s***! Why don't they just turn on the disco music?" I remember thinking "What? You crazy? We're the Vikings. Everyone loves the Vikings!" It really hit me then that things were going to be different from what we were used to.

The struggle intensified to a different level. After being holed up for a year, we were suddenly in a position of trying to satisfy the record-buying public. And we weren't doing a very good job of it.

There were several reasons for this. We were not a clearly defined band; our material ranged from our own album material to current and past cover songs to some of the old Vikings tunes. We were trying to satisfy everyone and, in the process, we were satisfying few. Most importantly I finally admitted to myself: I just wasn't comfortable doing a lot of this new material.

It was not a happy realization. I knew that we were not in for an easy time of it.

At the 2001 gig, Fred fell off the stage. He didn't hurt himself; he quickly bounced back up. But we knew the months of relative inactivity had taken a toll on Fred. His love for Scotch was getting out of hand.

We had discussed the problem with him several times but now it was obviously time to take action. We insisted that he check himself into the Lewis-Gale alcohol rehab center.

Fred, who knew it was the right thing to do, agreed. And, as he did everywhere he went, he made friends with everyone there. Fred, who had taken several ghastly falls without injury in rather inebriated states, fell while playing volleyball at the rehab center while completely sober and broke his collarbone. Spent a few days in the hospital.

But when he checked out of the rehab, Fred was a new man. He was sober, had lost his tummy, and looked great.

Now all the attention was directed to the record release and concert, slated for February of 1985.

| Roanoke |

Having consummated the deal with IDN, Wes had the records pressed in L.A. I wrote the album credits but other than that we were not consulted about the album cover; it was designed by someone in L.A. and we were disappointed with the results. The colors were somewhat washed out and it looked ... well, independent.

It was the band's job to get the record in local record stores, no small job in itself. But most major stores cooperated and several even featured the album in their window displays.

Several weeks before the February concert we hand-delivered records to all local radio stations. Many played cuts from the album without hesitation.

Then there was K-92.

K-92 was considered a national powerhouse, one of the highest rated stations in the country; since it was a Top 40 station in our own hometown, Wes contended that K-92 held an important role in the record's success.

For this reason I approached the station to see if they would co-sponsor our concert, the proceeds of which would go to benefit the American Heart Association.

The man to contact was K-92's program director. For a week he would not return phone calls. Finally an assistant called back and, after more time and more phone calls (I never did talk to the program director), K-92 agreed to co-sponsor the concert with American Heart. I am sure they did this strictly for political reasons; certainly they never had any real interest in the band. I would imagine that the powers that be at K-92 considered us a bunch of over-the-hill musicians and resented the fact that there was any obligation on their part to be involved.

That was fine; I could certainly recognize that point of view. I only wish they had been honest from the beginning and stayed out of the project. Working with them was degrading; I would have broken ties with them several times had it not been for Wes' insistence to "Be nice to them ... don't make anyone mad. They're important to us."

Working with K-92 was a lesson in game-playing.

Wes had decided that the first single off the album would be a song called Heart On The Line. The concert was called the "Heart On The Line Concert" (thus the tie with the American Heart Association) and that was the song we wanted to push.

But K-92 said they liked another song, Nothing's Wrong, and they would play it only if they had a reel-to-reel copy dubbed directly from the master tape. This was ridiculous, because I had a high-quality copy in hand, but they insisted. We had the song copied from the master in L.A. and it was FedExed to the station.

The song was never played.

K-92 finally agreed to play Heart On The Line, but only if it won the "Battle of the New Sounds," a weekly competition during which listeners called in to vote on their favorite of several newly released records. We were assured our song would be played the following week.

Needless to say, we had lots of friends listening and naturally K-92 knew that. The record wasn't played. Sorry, they said, there was a mistake. It would definitely be aired the next week.

It wasn't.

The same assurances were made for the following week.

No "Heart On The Line."

The fourth week they finally played the song. It was up against major artists and strong material. Heart On The Line won the contest by an embarrassingly large margin.

| Tom Bahler in 2000. Tom wrote Bobby Sherman's Julie Do Ya Love Me. Photo compliments of www.cmongethappy.com. |

After that, K-92 did put the song on their playlist and it even made their chart ... but we didn't feel good about it.

Since they were co-sponsoring the concert, K-92 had agreed to give it strong on-air promotion. And since it was a charity event, we were depending heavily upon K-92's publicity.

We monitored the station consistently and, one week before the concert they had done next to nothing. We found it necessary to buy a $1,500 schedule on the station that was sponsoring our concert.

This is not meant to reflect upon the current personnel at K-92; and I do not believe that the late Aylett Coleman, then-owner of the station, knew any details of what was happening. (Wes: "Don't go over anyone's head.") And many of the DJs, particularly Bart Prater, Vince Miller and Larry Dowdy, were our friends and allies. We were only allowed to speak with a smug few who answered to the program director.

I know that a certain amount of "irreverence" often increases the popularity of Top 40 stations but this went beyond that. Dealing with K-92 was a nightmare. I mention the K-92 fiasco because it was just one more major hassle that we really didn't need.

Several weeks before the concert, the hype began. Roanoke was waiting to see what $670,000 would buy. We held a press conference and received a lot of media attention. Both the Roanoke Times & World News and the Roanoker magazine ran feature articles. Wes hired Rogers and Cowen, a huge L.A. promotional firm which handles big-name talent, to publicize the group nationally. Articles were published in USA Today, The L.A. Times, and others.

The band worked hard preparing for the concert. We had moved to more comfortable rehearsal quarters; suddenly things were moving fast.

There was much to be done in preparation for the concert. Lighting and sound equipment had to be rented, tickets printed and distributed, and promotional material designed and printed.

Wes spent this time in Florida, though he did stay in constant touch by phone. The band and some dedicated investors did the legwork.

The concert was to be held at the Roanoke Civic Center auditorium. We arranged to get the auditorium a few days before the concert in order to rehearse and set up the stage. Wes arrived. Representatives from Rogers & Cowen arrived. It was said that national news media would be present. The concert would be videotaped by a local company.

We hired Joe Neil, a friend and nationally recognized sound engineer from Atlanta to mix the sound for the show. Stage hands were assigned their duties, which included filling the stage with smoke at designated intervals.

I was a nervous wreck.

Two and a half years of waiting and preparation came down to this: a single concert. The pressure was enormous. My thoughts directly before the concert were, "Where did the fun go?"

| Roanoke in a Field. Leroy, Fred, Tommy, Joy, Allen. |

The concert was sold out except for a few seats in the back of the hall. All our investors were present along with many other community leaders. Our families and friends were there. The audience mix was interesting: among the gray hair there were curious kids drawn by the K-92 connection.

Given the conditions, I believe that the band did a credible job of performing. We were well-prepared and the friendly hometown audience seemed to truly enjoy the show. We performed a mix of album material, familiar pop songs, and a medley of old Vikings material. Because of the audience response, some of the "fun" returned. The concert received a generally favorable review in the Roanoke Times & World News.

So now the concert was history. But now what? Wes contended that we couldn't be booked on a national tour until there was a demand for the band, and that demand was dependent upon how well the album did on a national or regional level. It was time for another period of waiting.

"Song pluggers" had been hired by Wes and IDN to push the album with individual radio stations throughout the country. We received reports that it was indeed being played on a fairly large number of stations; most were in smaller markets across the country. I even did a few on-air telephone interviews with some of the stations.

In the meantime we had been asked by Roanoker Richard Hamlett to front his famous wife, Debbie Reynolds, at an upcoming Roanoke concert. Richard had always kindly taken an interest in the band. I went to their Roanoke home to discuss the show and found Debbie to be a wonderful lady. A news reporter had just left and when I entered, Debbie kicked off her shoes and said "Now I can relax. You're one of us." After discussing business, Richard played a video tape of some of Debbie's most famous movie scenes. It was somewhat surreal watching these familiar movies while the star graciously served hors d'oeuvres and cocktails. (Richard and Debbie have since gotten divorced.)

At Debbie's concert we played as an opening act for about 20 minutes. Then 52, Debbie proceeded to put on an energetic and very entertaining show.

The band played several shows and dances during this period but most of our time was spent waiting to see how the record fared with the buying public. This wait, however, was not a long one. After a few weeks had passed it became apparent that the single, "Heart On The Line", was not a hit record.

We released another single, "A Little Less Smoke." But it was too late. The hype was finished. The show was over.

Faced with this knowledge and a dwindling bank account, we voluntarily took a 50 percent salary cut and released our three sidemen. This was hard to do: these guys ... Bruce, Ray and Audie ... had done a great job and we had become good friends.

In June of '85, two months after we had released the sidemen, Wes called with news that a pilot TV show called "Rock Showcase" was being taped in New York and the producers wanted us to be one of the four or five bands to participate. We hastily reassembled the band, rehearsed a few times, and headed to New York for the taping.

| Wes with David Cassidy. According to a 2000 interview with Tom Bahler, David, too, ran out of patience with Wes. Photo compliments of www.cmongethappy.com. |

This was an interesting trip. The set was in a rented warehouse and a lot of money was obviously being spent ... though not on us. We did the gig for free. The headline band consisted of Paul Butterfield and a variety of excellent musicians. The other bands, like ourselves, were in the process of trying to get established; one difference was that they were all very young. They looked like rock stars, with their exotic costumes and freaky hairdos.

I thought we performed well on the show. The people in charge seemed pleased and we left feeling good about the experience.

We never heard from "Rock Showcase" again. Matter of fact, we never even saw the tape.

In an attempt to salvage the project, the band spent the summer of '85 writing and recording demos of our own material, this time "Vikings style." Allen and I made a couple of trips to Nashville to push the songs and the group and we did attract some interest.

But we were tired. The years of frustration had taken their toll; we had been knocked down once too often. It was time to lay the band to rest and move on.

The band members went back to their old jobs or found new ones. The small amount of money remaining was distributed back to the investors. The band "Roanoke" was history almost three and a half years after the idea was conceived.

We had never experienced this kind of failure before, and it was difficult to face people, especially in Roanoke where everyone knew the story. Our investors, however, were wonderful. I personally heard few negative comments from any of them.

So why didn't this venture work?

In the first place it was a "crapshoot" from the beginning. There are enormous amounts of very talented people competing for the "big time" and success depends upon a complicated mix of factors, luck being one of the major ones. Having the money did give us some advantage and $670,000 is a lot in anyone's book. But that amount is relatively small compared to money that is spent in the industry; even in 1984 some music videos alone cost a million and more to produce.

In retrospect, there are most certainly things we should have done differently. The most obvious was our decision ... or perhaps I should say Wes' decision ... to do the rock material. We should have objected more strongly; the excitement of the moment simply overcame common sense, and we ended up losing the essence of the Vikings' own unique talents; we became a manufactured band.

Was hiring Wes Farrell a mistake? Perhaps. I know that Wes wanted the venture to be successful but I believe that he wanted the success for himself more than he did for the band and the corporation. I did not like his method of producing the record, nor did I like the way he managed the band. Wes never really looked at the kind of band we were; he insisted on making us into what he thought we should be. I believe that our biggest mistake was agreeing to allow Farrell complete control; the band members' experience and common sense should have been allowed more precedence in key decisions.

| Wes and legendary producer Bob Johnson, who dropped by Treasure Isle to see Wes during the session. |

At the same time, Wes did have his strengths. He knew the people to hire; the studio, the studio musicians, Tom Bahler, Rogers & Cowen, even our make-up artist were all first-rate. His methods of handling things, while we disagreed with many of them, had worked well for him in the past. And the truth is, even with our differences, it was hard not to like Wes. He was personable and often fun to be with. I should add that I think Wes produced a pretty good album; I am not at all ashamed of it, for what it is. It just isn't the Vikings.

It is possible that the venture didn't succeed simply because we just weren't good enough. I believe, however, if we had received certain breaks and if we had taken alternate turns on occasion, we could have been competitive.

I suppose that a volume could be written in hindsight about the things we could have done differently. But all decisions appeared right at the time and I see no need to defend them further.

I will always be grateful for our investors' monetary involvement in our project and I'll always appreciate their belief in the band. The backers invested their money and the band members invested three years of their lives; I believe that's fair and equal compensation on both sides.

In the spring of '86 we decided to get back together with the original band members and have another Vikings reunion; the 2001 nightclub was booked for the weekend of June 20. We hoped to recapture some of the old magic of the 1982 reunion, if only for one weekend.

It was not to be.

On Friday, June 13, 1986, my phone woke me up abruptly at 5 a.m. It was John Andrews , the all-night DJ at WROV, who informed me that there had been a fire at Fred's apartment and I should call Roanoke Memorial Hospital. John was visibly upset and said that Fred was badly hurt.

I called the hospital and informed them of Fred's next of kin, his daughter Whitney who lived in Galax and his brother Chris, who lived in Kansas City. The hospital personnel would give no information on Fred's condition until the next of kin had been contacted; even then I refused to believe the worst. But sadly, when I called back 30 minutes later, they informed me that Fred had been dead on arrival. He had died of smoke inhalation.

| The Reunion that was Not to Be. The Vikings, June 3, 1986: (back) Grant Ellis, Fred, Lane, Tyler; (middle) Allen, Leroy, Tommy, Ralph; (front) Joy, Ann. |

While dealing with my own initial shock and disbelief, it occurred to me that there was no one besides myself to handle the dreadful job of informing people of the news. My first thought was to call Fred's fiance, Vickie King, before she heard it on the radio. Through a set of circumstances, this fell to my then wife-to-be, Glenn Englebert, who was with me through the ordeal.

There were many other people to call: the band members, Fred's close friends, and others. At 6 a.m. I numbly began to make the calls. It was, to say the least, a terrible experience.

Soon after 7 a.m. when the news hit the airwaves, my phone began to ring. For eight hours I took calls, my call-waiting tone constantly interrupting each. The calls came from friends, casual acquaintances, the media, and people I didn't know, some hysterical. The newspaper interviewed me, TV stations wanted tapes, wanted me to go on camera; I declined. Many of the phone calls were those that would normally be made to a grieving family and I realized, more than ever, that the band was Fred's family.

I know that Fred would have wanted his funeral to be a party with lots of music and champagne but our grief was too much for that. Fred's long time DJ partner Jack Fisher, Allen, friend John Hartmann, WROV owner Burt Levine and I gave tributes at the memorial service. Jack's was especially emotional. Virginia's then-Governor Jerry Baliles, who had worked with Fred, sent a touching letter which was read at the service by the late Reverend Harry Gamble, who officiated at the funeral.

The next week, Mayor Noel Taylor issued a glowing mayor's proclamation in honor of Fred. I hope Fred was around to see all the accolades presented and love expressed to him from the community he cared so much about.

The Vikings don't perform much anymore, but when we do get together it's like a family reunion and the fun has returned.

We're missing a family member, but each time we play, somewhere between City of New Orleans and Old Blue, you might hear an echoed voice singing:

"Mr. Bojangles ... that man could dance."

Since 1995, when this article ran in the Roanoker Magazine, the Vikings have played a couple of sold-out reunion weekends at the Coffee Pot and saw in the millennium singing at a big party at Hotel Roanoke. The band last performed in late 2003 at a reunion concert featuring several popular bands including the great Royal Kings. We're in our early 60s now, and it's doubtful we'll play again. But we'll never say never!

Wes Farrell died in 1996 at the age of 56.

—Tommy Holcomb